TICKET SALES TERMINATED

Tickets are currently unavailable on TicketWeb

Bluebird On 3rd featuring Jaimee Harris, Kim Richey& Tony Aratawith Katie Pedersonand Mike Kinnebrew

Mon, 13 Oct, 12:30 PM CDT

Doors open

11:00 AM CDT

3rd and Lindsley

818 3rd Ave. S, Nashville, TN 37210

TICKET SALES TERMINATED

Tickets are currently unavailable on TicketWeb

Description

Please be aware that "Bluebird on 3rd" shows take place at 3rd & Lindsley Bar & Grill, located at 818 3rd Ave S, not at The Bluebird Cafe.

Event Information

Age Limit

All Ages

Singer-Songwriter

Bluebird On 3rd

Bluebird On 3rd

Singer-Songwriter

Americana

Jaimee Harris

Jaimee Harris

Americana

Jaimee Harris turned 30 during the pandemic. It’s a milestone that is a rite of passage even during normal times. But for this Texas-born singer-songwriter, it came in the midst of one of the strangest and most tumultuous periods in American history. When the world stopped during lockdown, Harris, like many others, found herself gazing back into the past, ruminating on the nature of her hometown and family origins, and reckoning with their imprint on her. The term ‘nostalgia’ derives from the Greek words nostos (return) and algos (pain), and if Harris’s Boomerang Town can be regarded as a nostalgic album, it is only nostalgic in the sense that the longing for home is a desire to return to the past and heal old wounds.

“I’m at an age where I’m wrestling with trying to understand the nature of my family,” Harris says. “There’s been suicide, suicide ideation, and there’s certainly been addiction all through my family. My dad’s father died of suicide when he was 25 and I was 5. I couldn’t imagine not having my dad right now.”

Harris’s sophomore effort, Boomerang Town marks a bold step forward for this country-folk-leaning singer-songwriter. It is an arresting, ambitious song-cycle that explores the generational arc of family, the stranglehold of addiction, and the fragile ties that bind us together as Americans.

For Harris, the album began gestating around 2016, a time of great loss for many in the Americana community, with the songwriter losing several musicians close to her. The shift in the nation’s political landscape had ushered in a new level of polarization that saw whole swaths of cultural life being demonized. For someone who grew up in a small town outside of Waco, Harris believed the values instilled in her by her parents were not entirely in line with how many on the left were viewing — and vilifying — Christians, citing them as responsible for the new change in leadership. As a person in recovery, Harris has had to re-evaluate her own connection to faith and find strength in a higher power (“Though he’s not necessarily a blue-eyed Jesus,” she laughs), though she certainly knows what it’s like to “be told how to vote” in a Southern church setting.

It was from the intersection of these social, personal, and political currents the album was born. And while much of the material on Boomerang Town was inspired by personal experience, the songs on this collection are far from autobiographical xeroxed copies. More than anything, they come from a place of emotional truth.

Boomerang Town traces the fortunes of a host of characters who live on the knife’s edge between hope and despair. The title track, whose sound recalls the best of Mary Chapin Carpenter’s ’90s work, features a young couple from a small-town working dead-end jobs who get “knocked up” and have their dreams put on hold. It is a portrait of rural desperation and the restless search for salvation against long odds. “This is what it’s like to be a part of the post- “‘Born To Run’ Generation,” Harris quips. “Springsteen’s generation had somewhere to run to. I’m not so sure mine does.” For the characters in these songs, escape isn’t always a matter of geographical distance.

“I tried a lot of perspectives [on this one],” Harris says about writing the title track. “My parents are high-school sweethearts and I was an accident and they’re still happily married. I worked at Wal-Mart when I was 19. I reflected on this guy who was the brother of a good friend of mine. He didn’t drop out. He knocked up his girlfriend and went into the military. Certainly [the song] is a combination of me and not me. It was me thinking about what might have gone differently for my parents, who are still in Waco and own a business there.”

Harris’s father, whom she counts as a big supporter and responsible for much of her musical education, took her to the first Austin City Limits Music Festival, where she had the life-changing, Eureka moment of seeing Emmylou Harris, Patty Griffin, and Buddy and Julie Miller perform on stage at the same time. It was then the young Harris knew what she had to do. She had found her ticket out.

Harris continues: “Why was I able to get out of my boomerang town? Why are others stuck there, longing to leave but unable to find their way out? Writing these songs, bringing these narrators to life, brought me closer to the answers,” she says.

Themes of grief and addiction permeate other sections of the record. “How Could You Be Gone,” which Harris wrote with her partner, the venerable folk songwriter Mary Gauthier, reflects on the passing of a close friend during the pandemic, as well as the 2017 death of Harris’s mentor and compadre Jimmy LaFave, a long-time fixture on the Americana scene who succumbed to cancer. “It’s been my experience that grief operates on its own timeline,” Harris says. “I wanted this track to build and repeat with intensity to mirror the experience of relentless grief.” Another song, “Fall (Devin’s Song),” is about a former childhood classmate of Harris’s who was accidentally shot and killed in the sixth grade. The song was inspired by a series of “In Memoriam” pieces the boy’s mother wrote to the local paper, and the song serves as a tribute to both of them, as well as a commentary on the timeless nature of grief.

One of the album’s standout tracks is the lilting, Irish-influenced “The Fair And Dark Haired Lad,” a Chicks type-number that grapples with the seductive nature of alcohol. Another tune that deals with the demon rum, “Sam’s,” is far more dirge-like, and its dark, circular melody mirrors the claustrophobia and sense of trapping that comes with the onset of addiction and mental collapse.

Boomerang Town is not entirely a lament, however, with songs like “Love is Gonna Come Again” and the wistful “Missing Someone” shining with hope in the face of the darkness. For this is a record that understands that love and grief are two sides of the same coin. It also announces the arrival of a great new songwriter on the scene.

“My goal is to just write the best possible song I can write,” Harris says, “and I wanted to have ten songs that made sense together sonically. I still believe in the album format, and I wanted to lay the groundwork as a solid songwriter.” On Boomerang Town, Jaimee Harris, who was able to find her way out — unlike so many others — has accomplished all that, and much more.

Music

Kim Richey

Kim Richey

Music

“I started off that record scared to death,” Kim Richey recalls of making Glimmer with producer Hugh Padgham back in 1999 in New York and London. A disastrous haircut, unfamiliar musicians, and oversized budgets didn’t help matters. “It wasn’t the way I was used to making records.”

The way Richey was used to making records was with friends in a vibed-out, low-key setting. That’s how she made her debut album with Richard Bennett, and it’s how she made her new album, Long Way Back… The Songs of Glimmer, with Doug Lancio. So Glimmer was different, and not just on the production side.

Then, as now, the compositions that comprise Glimmer were the Grammy-nominated singer/songwriter’s first collection of true confessionals. Prior to that she’d been a staff writer at Blue Water Music writing from a more arm’s-length vantage point for her first two releases, 1995’s Kim Richey and 1997’s Bitter Sweet. But Glimmer was all her.

Revisiting that history for A Long Way Back was both emotional and edifying for her. “I was pretty broken-hearted when I wrote and recorded most of those songs and I remember feeling that way,” she says. “At the time, I needed to really get out of my head and out of Nashville. I think that was what appealed to me so much about making a record somewhere that wasn’t home and with new people. Recording these songs again was a good way to look back and remember I made it through those times.”

The 20 years of distance between then and now provided another benefit, as well: Richey is more comfortable with her voice, both literally and metaphorically. As a result, Long Way Back sounds like it has nothing to prove and nothing to hide. It’s more spacious, but not less spirited, with Richey’s voice, in particular, feeling more relaxed and rounded than on the original. Starting with “Come Around,” the 14 new renderings take their time to make their points, meandering casually around, much like their maker.

An Ohio native, Richey’s passion for music was sparked early on in her great aunt’s record shop where she’d scour the bins and soak it all in. She took up the guitar in high school and, while studying environmental education and sociology at Western Kentucky University in Bowling Green, she played in a band with Bill Lloyd. But it didn’t stick… not right away.

After Kentucky, Richey worked in nature centers in Colorado and Ohio and traveled to Sweden and South America. She eventually landed in Bellingham, Washington, where she worked as a cook while her boyfriend went to grad school. Their deal was, she got to decide where they went after he graduated. One night in 1988, some old friends — Bill Lloyd and Radney Foster — rolled through town. She sold t-shirts at their gig, and they talked up Nashville. To drive the point home, Lloyd sent her a tape with Steve Earle and others on it. So taken by the songwriting, Richey and her partner loaded up their Ford F150 and headed to Music City.

In Nashville, Richey cooked at the famed Bluebird Café and gigged around town at writers’ nights. At a show one night at 12t h & Porter, Mercury Records’ Luke Lewis approached her. In classic Richey fashion, she didn’t know who he was. Still, she went to a meeting with him and Keith Stegall, played one song, talked a lot, and got a record deal at the musical home of Billy Ray Cyrus and Shania Twain. Remembering the glory days of major labels in the ’90s, Richey says, “They gave me way more than enough rope to hang myself with. I could do whatever I wanted.”

What she wanted was to work with her friend, producer Richard Bennett. So she did. For Bitter Sweet, she put Angelo Petraglia at the helm, before turning to Padgham for Glimmer. “Bitter Sweet was recorded in Nashville with my road band and friends,” Richey says. “That record was as if the kids had taken over the recording studio while the adults were away. Glimmer was more pro and less messing around having fun. The musicians were all super-talented and gave the songs a voice I never would have thought to give them. Hugh was up for trying anything and really encouraged me to add all those vocal arrangements that ended up on the record”.

For 2002’s Rise, Richey took another left turn, signed to Lost Highway Records, and hired Bill Bottrell as producer. Though it was her first time writing in a studio with a band, the players’ talent and Bottrell’s whimsy proved to be great complements to Richey’s own rule-breaking style. The resulting record was quirky, confessional, mesmerizing, and masterful. And it officially set her outside contemporary country’s bounds which was fine by Richey, whose music had always broken barriers.

A greatest hits collection dropped in 2004, buying her some time to tour, write, and make 2007’s Chinese Boxes with Giles Martin in the UK, followed by 2010’s Wreck Your Wheels and 2013’s Thorn in My Heart, both produced by Neilson Hubbard in Nashville. The latter landed her at Yep Roc Records, where she also released 2018’s Edgeland, made with producer Brad Jones in what she has described as the easiest recording process she’s ever had, despite working with three different tracking bands in the studio.

Through it all, Richey has worn her heart on her lyrical sleeve, revealing herself time and again. “I started writing songs because of Joni Mitchell, probably like most women songwriters of a certain age,” Richey confesses. “I loved being able to write songs because I was really super-shy. I couldn’t say things to people that I wanted to say. If I put it in a song, there was the deniability. If I ever got called on it, I could say, ‘Oh, heavens no, that’s just a song! I made that up.’”

Though she could fall back on plausible deniability, with Richey, what you hear is actually what you get. “I don’t have a lot of character songs because I’m not that good at making things up out of thin air.” Even when it comes to the main narrator of a song like Edgeland’ s “Your Dear John,” Richey demurs with a laugh, “I do think that song is probably just another song about me and I’m pretending to be a barge worker.”

On Long Way Back… The Songs of Glimmer, though, she’s not pretending to be anything or anyone she’s not, and neither are the songs. Richey and Lancio set out to make a guitar/vocal record, but the songs had something else in mind, and that something included drums by Lancio’s legendary neighbor, Aaron “the A-Train” Smith, among other things. “Once we stopped making rules about what could and could not be on the record, the songs spoke for themselves,” Richey says. “I knew all along I wanted Dan Mitchell to play flugelhorn, and the two tracks he played on are two of my favorites. In the end, the songs decided.”

From her move to Nashville to her making this record, for Kim Richey, the songs have always decided.

Music

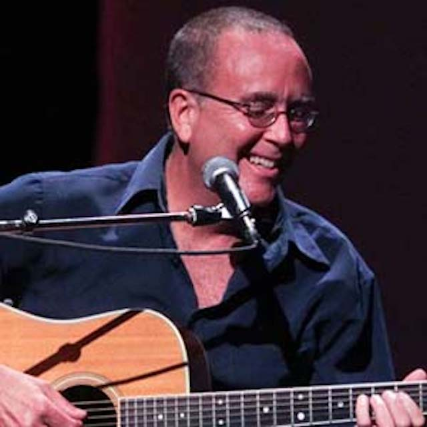

Tony Arata

Tony Arata

Music

Nashville Songwriters Hall of Fame member. Grammy nominee.

Songs: The Dance - Garth Brooks, Dreaming with My Eyes Open - Clay Walker

Country

Katie Pederson

Katie Pederson

Country